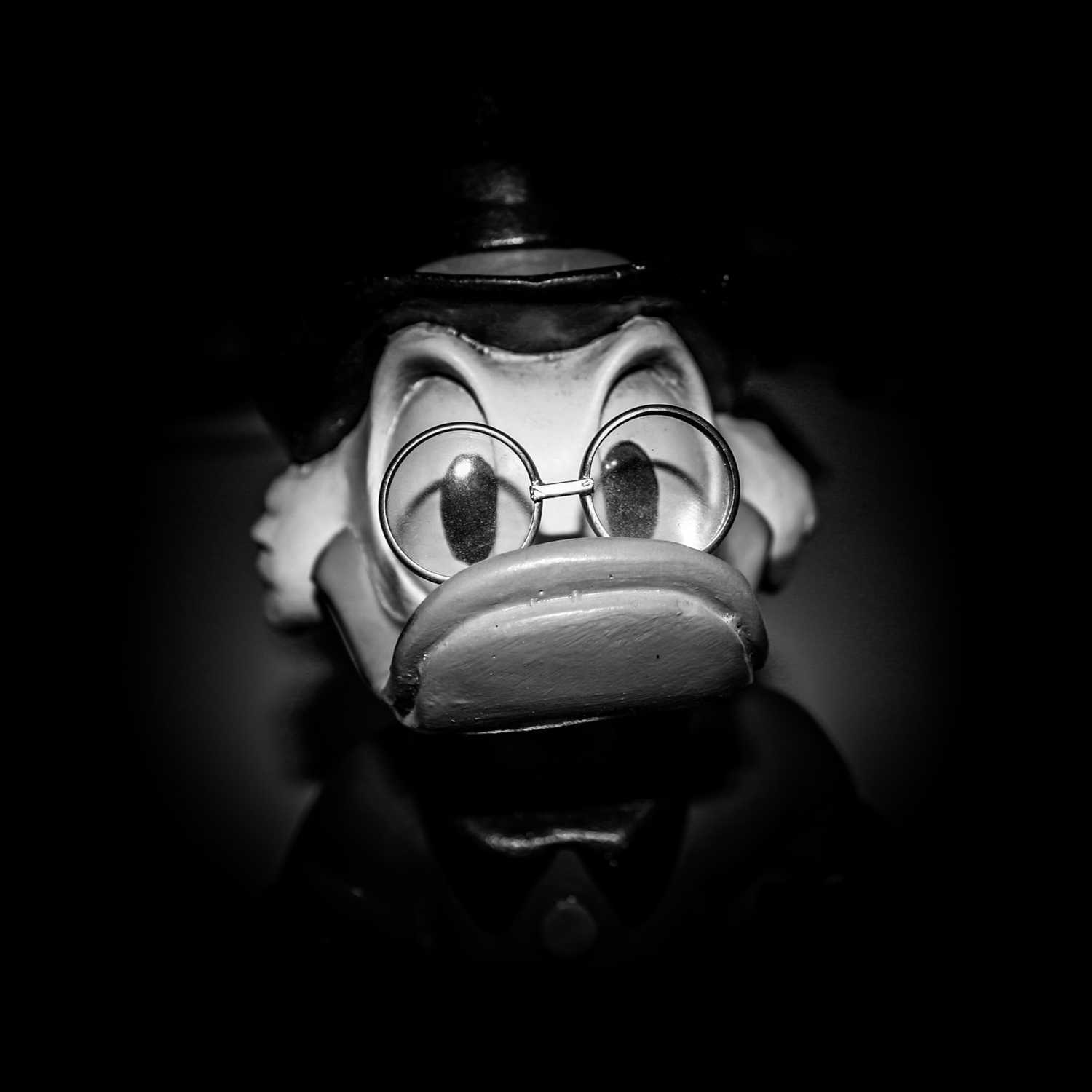

With the essay Tales of Inequality: What Piketty, Rousseau, Scrooge McDuck, and the Devil May Have in Common, Florian Willems and I won an essay prize of the University of Cologne in 2020 (prize contest: 'What is the Future of Inequality among People, and How Can it be Changed by Social and Cultural practices?'):

What do Scrooge McDuck, the Roman Gracchi reforms, Martin Luther, the 1754 Academy of Dijon’s call for essays on ‘What is the origin of inequality among people, and is it authorized by natural law?’, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau all have in common? And Thomas Piketty, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s (1925) The Great Gatsby, Karl Marx, and the Devil? In one form or another, they express, or are expressions of, moral concerns about inequality. These and many other historical and fictional figures, such as the legend of Robin Hood, are indicative of the fact that our past and present is riddled with moral disquiet about a lack of sharing, egoism, greed, hubris, ‘unearned’ wealth, and many other qualities associated with unequal advantages – notwithstanding that other forms of inequality are simultaneously very much present in many tales and myths, such as in the case of Greek Gods.

At first blush, these examples resemble a mixed bag, as they range from (non-)fictional religious and mythical figures and folklore to modern academic research. The empirical grounding thus varies substantially, with Piketty providing a meticulous account of increasing inequality in our era. Rousseau made an equally academic attempt to account for the origins of inequality, with the shift towards sedentary agriculture considered the primary source of inequality in human societies. Hunter-gathers, conversely, are often perceived as the epitome of egalitarianism, which as anthropologist Marshall Sahlins (1972; 2017) has demonstrated, is only true to a certain extent. But whether or not inequality is virtually absent or weighs heavily on society, mythical figures, religious principles, and popular tales opposing (too much) inequality have never ceased to exist. Scrooge McDuck may be a fictional cartoon character, yet, like his namesake Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens' (1843) A Christmas Carol, he is a reflection of societal objections against the egoistic and cold-hearted rich. Equally, much of the social scientific literature, from analyses of egalitarian societies to the current body of research on inequality seem to have sprung from the same long tradition of moral concerns about inequality and their representation in fiction and theory.

Notwithstanding insightful analyses that have emerged from empirical investigations, such as Piketty’s (2014), about why inequality increases, what the negative societal impacts of inequality may be, and so forth, there is surprisingly little discussion about the (historical) workings and logics underlying our seemingly pervasive moral concerns about inequality. Perhaps because many of us have been taught early on in our lives that greed, egoism, and a lack of sharing are vices, we take moral objections against inequality for granted and refrain from analysing them. Closer investigation, however, may reveal that the scientific body of literature, our upbringings, religious principles, and popular narratives may have more in common than meets the eye. They may in fact constitute a long history of structuring concerns about inequality – that apart from providing insights about the past and the present, may also be of relevance to the future.

It might be that raising concerns about inequality, and exerting pressure for a redistribution of wealth, is nearly a universal human tendency – if not expressed through physical force, as with the cases of the French or Russian Revolutions, then at least through the everyday disapproval of behaviours associated with the rich and powerful. Such disapproval often occurs behind the backs of the wealthy, for as the example of the Gracchi Brothers in 2nd century BC Rome demonstrates, there can be real danger in openly confronting the rich and the mighty (see also James C Scott’s (1985) Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance). In other words, the existence and acceptance of inequality may be mutually exclusive. Many myths, narratives, and customs around the world seem to indicate that inequality is rarely easily accepted. In some instances, such as in novels like The Great Gatsby, elite decadence is the (indirect) target of moral disapproval, while in other stories, doom and hellfire will be the fate of those who solely think about themselves and refrain from sharing with fellow human beings.

Of course, it could be argued that the effects of moral tales and concerns are limited. After all, according to a 2019 Oxfam report, the world’s richest 26 individuals nowadays own the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of humanity. Yet, and without denying the (unequal) reality, we argue that we should not dismiss the impact of moral tales too lightly. Or at least, we make a plea for more research on the origins and workings (or lack thereof) of, on the one hand, moral admiration of sharing, reciprocity, altruism, and egalitarianism, and, on the other, moral disapproval of greed, hubris, selfishness, envy, and so forth. It may be that in virtually all societies, both historically and across cultures, moral objections against people who do not share parts of their possessions and rewards are persistent, whether these are gathered food items or financial wealth. The ‘need’ for moral tales admonishing inequality, at the same time, indicates that human practices leading to inequality are widespread and varied. Why otherwise go to such great lengths instilling fear for figures such as the Devil? A better understanding of the essence and workings of these moral tales, as well as the various accounts that ‘justify’ the breaching of moral principles, may contribute to grasping how social and cultural practices (or discourses) can work in favour of reversing inequality – starting with the rich.

Even the rich can’t walk away from it

Just as the wealthy and powerful reap the benefits of inequality, many seem to feel a need to stress that they are not selfish, cold-hearted actors like Ebenezer Scrooge, but that they care about their fellow, poorer human beings; or, they emphasise that their selfish behaviour is in fact beneficial to society at large (e.g. as ‘job creators’). Their arguments and practices indicate that they are very much aware that too much inequality is not only poorly perceived, but also a threat to their wealthy status. Although such awareness certainly differs from one society to the next, with the seventeenth-century Russian feudal lords demonstrating especially cruel behaviour towards the poor, hardly anyone seems to openly admit that their virtue is egoism in its purest form. And if the rich do not justify their position vis-à-vis the poor, then at least they appear to be concerned about how their peers perceive their ‘generosity’. Hence, in the analysis of the workings of tales about sharing, egoism, egalitarianism, and inequality, the discursive responses and strategies of the rich and powerful also need attention – whether through religious parables or in actual history. Their justifications, and how these reflect dominant discourses about inequality, may provide insights about the persistence of inequality; next to all kinds of other practices that create and facilitate inequality, such as violent suppression, conspiracy, and tax loopholes.

Even in highly unequal societies that value individual wealth, such as in the contemporary U.S., many rich people still feel the implicit need to give accounts about their contribution to society at large, and/or to ‘redistribute’ part of their wealth. Philanthropy is one of the fig leaves aimed at convincing others that their wealth is for the greater good. Although it has been demonstrated that philanthropy serves the givers rather than reversing inequality (e.g. Giridharadas 2019), the existence of philanthropy indicates that the wealthy cannot ignore widespread (and long existing!) moral concerns about inequality. The wealthy do not operate above and beyond widespread beliefs about inequality, and thus openly stating that they do not care about others is hardly an option. Even the ‘rational’ but essentially egoistic Homo economicus can only be egoistic insofar as its self-interest is beneficial to society at large, however far-fetched that may be. And when the rich get richer, there is always the argument that their wealth will eventually ‘trickle down’. Although these arguments have little bearing with reality, they show that neither (neo)classical economics nor the wealthy in the United States (and beyond) can ‘escape’ moral tales about inequality, as they are compelled to accommodate such tales in theories and justifications about the advantages they enjoy.

Philanthropy, charity, and other ways of appeasing the poor are not mere inventions of capitalist society, however. They have much longer histories, which that indicate that unequal material wealth has often suffered an uncomfortable status in society. Ancient Roman ruins, for example, bear inscriptions with the names of those who originally financed their construction. Contrary to Donald Trump’s contemporary fixation with displaying his name on skyscrapers and hotels of his own, these buildings were not the private residences of wealthy Romans. The inscriptions were instead found on public buildings, which demonstrates that there was already a tendency among the rich to publicly display their support for the greater good, whether by supporting necessary infrastructure or, as was the case with the eponymous Gaius Cilnius Maecenas, for the arts.

Notwithstanding the variety of examples demonstrating our point, the question remains as to whether or not ‘concerns’ about inequality and appeasing the poor (even absent any serious redistribution) are historical exceptions in a vast ocean of other examples of selfishness and severe suppression. We can by no means provide an all-encompassing answer, although it is striking that even rulers who protect their dominance with violence often still justify their position with reference to the common good. Kings and emperors have long argued that they are the earthly representatives of gods that serve society at large. Hierarchy and inequality at the service of humankind, so to speak. Aztec rulers sacrificing human beings, for example, may be considered particularly cruel and unjust from a contemporary perspective. Scarifying human beings, moreover, undoubtedly served the confirmation of their power. Yet even these rulers justified their cruel practices with reference to the benefits for the whole of society; gods needed to be pleased and appeased in order to bring better weather that would be beneficial to all. Paradoxical as it may seem, powerful actors who clearly and openly argue that they stand above the common (poor) people, the plebs, may still feel the need to stress that what they do has a wider social relevance and justification. The question is why this emphasis, since it could be argued that they need not be concerned with the masses? Equally, racists regimes, such as South Africa’s Apartheid and the Confederate States of America tended to refrain from stating outright that they discriminated in order keep everything for themselves. Instead, they argued that it was also in the best interest of the suppressed (e.g. Wale and Foster 2007). Thus, even in suppression an awareness of rejecting unbridled egoism is often manifested.

The ‘natural’ law of opposing inequality?

Although the rich cannot often ignore moral concerns about inequality, the persistence of inequality indicates that the wealthy often get away with only paying lip service to the greater good. Yet the have-nots cannot be ‘fooled’ all the time, as a long list of historical uprisings demonstrates. The 16th-century Reformation, the 1524-1525 German Peasant War, the 1789 French Revolution, the 1796-1804 (Chinese) White Lotus Rebellion, the 1905 and 1917 Russian Revolutions, and the numerous revolutionary movements across Latin America across the 20th century, provide just a few of the more or less successful attempts to reverse inequality. Over time, many of these events and their protagonists have become part of the tales, legends, justifications, and warnings that are recounted about inequality. Characters like Karl Marx and Che Guevara continue to inspire uprisings and instil fear among the rich. The extent to which Piketty has also been picked up in moral tales seems to indicate that his own story (and empirical evidence) is also quickly becoming part of the ‘inequality narrative’.

In the analysis of tales about inequality, the legacies of uprisings and how their supporters and (intellectual) leaders live on in popular memory, both positively and negatively, are also of relevance. They may be important components of common sense-making. Depending on one’s perspective and position in the socio-economic hierarchy, references to specific events, protagonists, and antagonists may function within moral arguments that challenge or support existing inequalities. On the one hand, they may provide hope that change is possible, or comfort about one’s disadvantaged position: you may be poor, but at least you are morally superior to the rich, since you act according to principles of solidarity and do not merely act out of self-interest. On the other hand, it cannot be denied that the rich also have their own more-or-less specific events, protagonists, and antagonists in their own moral tales, albeit the other way around. The collapse of communism, and the authoritarian tendencies of many ‘communist’ leaders, may have been a blessing in disguise for them, as these figures easily serve to refute demands for a more egalitarian society. We may have inequality, but challenging the existing order may be worse, or so the story goes.

To better understand human practices in the shaping and challenging of inequality, in the past, present, and future, we have presented a call for more research on the origins and workings (or lack thereof) of moral tales about sharing, reciprocity, altruism, and egalitarianism, as well as just-so stories about greed, hubris, and selfishness. A focus on human practices is without doubt more fruitful in this endeavour than searching for natural laws. Yet, resonating with the original 1754 Academy of Dijon’s call, it may nevertheless be of relevance to speculate if opposition to inequality is a virtual ‘natural’ law, in the sense that there appears to be hardly any (historical and contemporary) society that is entirely at ease with inequality – as pervasive moral codes about sharing and other values seem to indicate. Much of the critique about inequality may still be indirect, and occur ‘below’ the surface, i.e. in tales, popular beliefs, legends, and cultural practices, such as child rearing. Disclosing the patterns involved, and the coherence and similarities between human practices, may offer an additional, and largely unexplored, angle to studies on inequality. It may be that most people consider inequality to be against the ‘natural’ order, by contrast with moral values of sharing, generosity, and so on. Even many rich people may raise their children with such values, thus potentially indicating that they also feel a certain discomfort about inequality. Investigating such questions is, of course, only one part of solving the puzzle, not the least because it is evident that the poor and rich alike often do not live up to their own values and ideals. Why, when many feel the need to (publicly) oppose inequality, do we not live in a more equal world, after all? This is a question that evidently links up with the search for the origins of inequality, and the extent to which inequality will always be with us as ‘natural’ law, central questions articulated both in the Academy of Dijon’s original call and Rousseau’s response. Even when it may be hard to come up with an all-encompassing answer, whether emerging from ‘natural’ law or human practices, some answers may lie in the extent to which moral objections against inequality are universal phenomena, perhaps expressing a ‘moral law’. It is from there that we may begin to grasp the reasons for an almost equally universal divergence from the ‘ideal type’. Revealing how widespread tales, religious principles, and other norms ‘against’ inequality really are may also allow us to reframe dominant narratives – in the future. When we can demonstrate that concerns about inequality are virtually universal, arguments in ‘favour’ of inequality – enabling policies, taxes, etc. – may become much more difficult to maintain. As a result, the world’s realities may instead come to resemble the ‘ideal type’, as envisioned by a universal moral law against inequality.

Bibliography

- Dickens, Charles. 1843. A Christmas Carol. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott. 1925. The Great Gatsby. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Giridharadas, Anand. 2019. Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World. London: Allen Lane.

- Oxfam. 2019. Public Good or Private Wealth? Oxford: Oxfam GB.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-first Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sahlins, Marshall. 1972. Stone Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine Atherton.

- Sahlins, Marshall. 2017. The original political society (the 2016 inaugural A.M. Hocart Lecture). Hau 7 (2): 91–128.

- James C Scott’s (1985) Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Wale, Kim and Don Foster. 2007. Investing in discourses of poverty and development: How white wealthy South Africans mobilise meaning to maintain privilege. South African Review of Sociology 38 (1): 45–69.